by Kirsten Chesney | Oct 20, 2020 | Nutrition

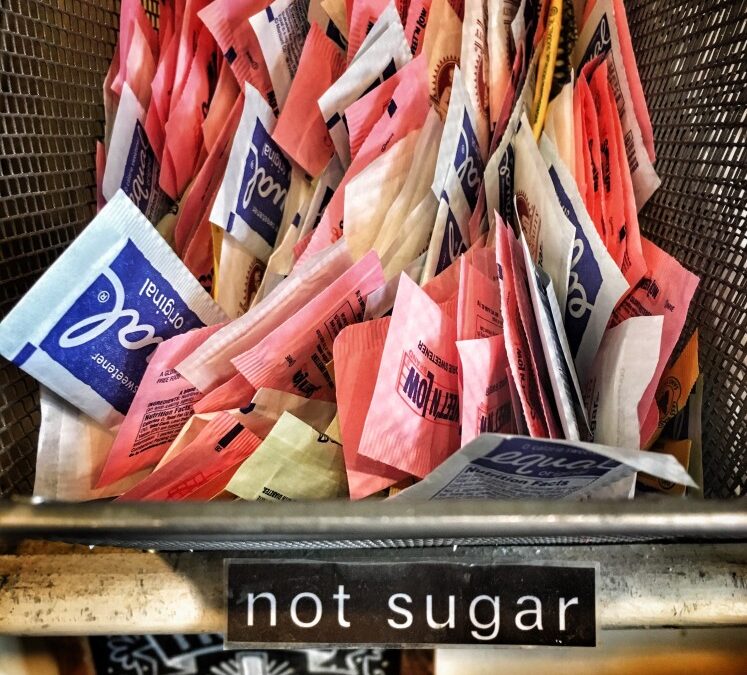

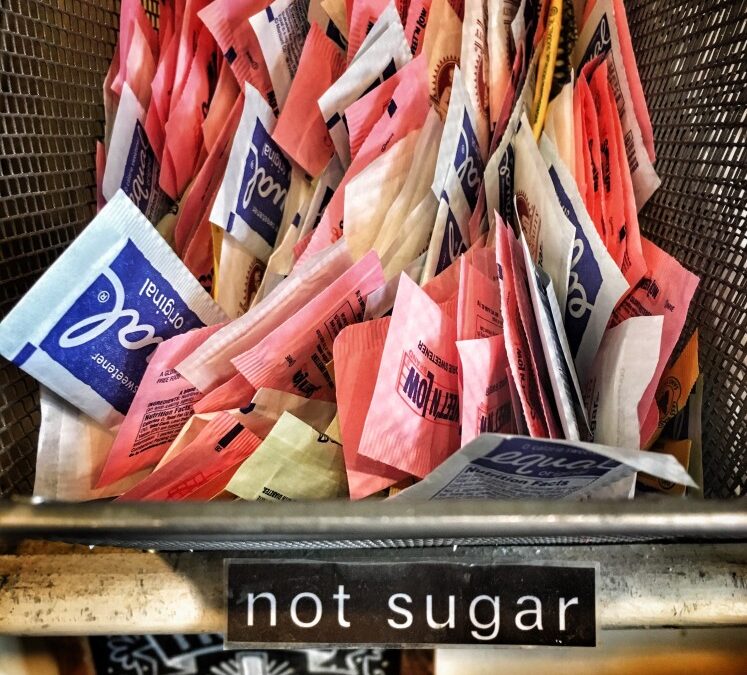

Artificial sweeteners may sound like the magic bullet for many people. This zero-calorie option provides all the sweetness but without the sugar. This is thought to lead to weight loss and a lowered risk of heart disease and type 2 diabetes. What could be better, right? After all, artificial sweeteners are encouraged by conventional medical doctors around the country. They’re also incorporated into standardized hospital meals for diabetic patients. Unfortunately, these facts don’t mean that artificial sweeteners are safe nor even effective against heart disease or diabetes. Let’s dig deeper to find out why.

Artificial Sweeteners’ Effect on Weight

Despite being zero-calorie, studies have shown that artificial sweeteners may actually increase overall daily calorie intake. Here’s how:

- After eating an artificially sweetened food, your brain may send you hunger signals. This is because it’s used to eating sugar-sweetened versions of food, which contain calories. Instead, your body is getting the same sweetness it’s used to, but without the calories. Studies show that people eat more artificially sweetened food compared to their sugared varieties before they feel full.

- Artificial sweeteners are more intensely sweet than table sugar or even high-fructose corn syrup. This over-stimulates the “sweetness receptors” of your tongue, which reinforce brain messages, causing increased cravings for sugary foods. At the same time, you may find less-sweet foods to be unpalatable (like legumes or vegetables).

So, whether you’re satisfying your hunger or calming your cravings, both of the above points lead to one common side effect: reaching for more food. In other words, artificial sweeteners can encourage people to eat more artificially sweetened foods (or sugary foods) to the exclusion of healthy, nutrient-dense foods. Shunning healthy foods in favor of sweetened foods inevitably leads to weight gain and increased risk for any and all chronic diseases, including heart disease and diabetes.

Artificial Sweeteners’ Effect on Disease

In addition to increased cravings and hunger, artificial sweeteners may actually increase your risk of developing chronic disease. However, this risk comes not through what you eat, but rather what you drink. The most common delivery method of artificial sweeteners into a person’s body arrives through diet soda. In fact, roughly 30% of American adults drink diet soda on any given day, typically to the tune of 24 ounces (or two cans) per day. Studies show that just one can of diet soda per day is associated with an 8%-13% increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Another study set that risk even higher, at 21%. Other than diabetes, diet soda has been linked to a higher risk of hypertension and heart disease. If this isn’t scary enough, drinkers of diet soda have a 36% increased risk of metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of conditions that include high blood pressure, high blood sugar, abnormal cholesterol, and excess abdominal fat. Those with metabolic syndrome are at risk of developing cardiovascular diseases and diabetes. Ironically, the most popular delivery method of artificial sweeteners leads to the very diseases that these sweeteners were supposed to protect against.

Another chronic condition brought on by diet soda is kidney disease. According to the National Kidney Foundation, those who drank more than seven cans of diet soda per week saw a doubled risk of developing kidney disease than those who consumed less than one can per week. This correlation was not seen in those who drank regular soda, leading scientists to believe that artificial sweeteners may be responsible. In fact, studies of those who drank diet soda saw a 30% reduction in kidney function over 20 years’ time compared to those who did not drink diet soda. It was further found that drinking two or more diet sodas per day caused kidney problems as opposed to drinking one can per day.

Artificial sweeteners, from any source, also damage the microbiome in our gut, killing off our good gut bacteria. This altered gut biome then leads to poor blood sugar control and increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Not to mention that the health of our gut plays vital roles in our immune system, mood, mental health, hormone balance, and much more.

Artificial sweeteners have enjoyed massive popularity in recent decades, with the claim that it can help you lose weight and lower your risk for diabetes and heart disease. It was an easy sell for manufacturers since it didn’t require any huge dietary sacrifice. Furthermore, it even enhanced the sweetness of our favorite junk foods. It seemed like the miracle drug. In reality, artificial sweeteners are too good to be true. Despite the positive outcomes and health benefits found in studies funded by the artificial sweetener industry, non-industry studies show the unbiased reality of the negative effects of these sugar substitutes. Not only do they lead to weight gain and increased sugar cravings, but they also invite a higher risk of getting several chronic diseases. Your best bet is to taper off any dependence on artificial sweeteners and added sugars, replacing them with whole foods that are nutrient-dense and richly fulfilling.

by Kirsten Chesney | Oct 8, 2020 | Nutrition

Eating healthy is tough when you aren’t even sure what’s healthy and what’s not! Too many people who strive to be healthy fall into the trap set by expert food marketers. They purchase what looks healthy based on the words or pictures on the package without questioning the motive behind it. As soon as a food can be altered by humans, there is money to be made from its sale and distribution. Notice there are no pictures, slogans, or ingredients lists on whole foods! This means that whenever you wander into the center sections of the grocery store, you are entering a marketer’s world. It is important to stay vigilant here since the advertising you see is expertly designed to appeal to your emotions, impulses, or brand-loyalty habits. Rarely do they highlight healthy qualities, nor are they backed by research. This is the minefield we will guide you through. Not only do we want you to spot advertising tactics meant to distract you, but also give you tools to gauge the true quality of food. We’ll first talk about misleading health claims and then move onwards towards the nutrition facts label and ingredients lists.

Health Claims to Be Aware Of

Before you flip over the box or bag and read the nutrition label, it is important to first gather information from the front of the package. If used properly, it can be a quick way to learn whether or not it’s worth purchasing. Only after the front of the package passes the test do you flip it to the back and see if it measures up.

The front of any food packaging tells you a lot of information and is the first step to helping you weed-out (or weed-in) the food. In general, most health claims on the front packaging should be viewed with caution. The purpose of any health claim is to get you to buy the product by making you think it is healthier than another, less flashy, brand. Manufacturers are often dishonest in their labeling and use misleading messages that appeal to emotion rather than fact. However, not all health claims are misleading, as you will find below. But it’s wise to learn which claims are supported and which are not.

Here are common health claims along with their underlying meaning:

Light:

This label means the food has one third fewer calories and less than half the fat than the original food. As great as this sounds, the process of removing fat usually involves the addition of sugar, flavor enhancers, and artificial ingredients. This is because naturally-occurring fat concentrates the flavor of food, making it taste good. Taking away that fat essentially robs the food from its original taste. Thus, manufacturers have to add sugar and synthetic ingredients to bring back the same taste consumers want. Regarding lower calories in the “light” label, there are more calories in fat than in sugar or other additives, so removing fat will naturally cause the calories to decrease.

Low-Fat:

Similar to the “light” label, above, any low-fat label usually means the addition of sugar and synthetic flavor enhancers.

Heart Healthy:

This label is put out by the American Heart Association (AHA) and is symbolized by a red checkmark. It can also be stated boldly by manufacturers without the AHA’s stamp of approval.

The problem with any supposed “heart healthy” products is that they contain processed vegetable oils (think of margarine). These oils are deemed heart healthy because they contain polyunsaturated fat (also called PUFA). While this is a healthy fat, it’s important to look at the type of PUFA. There are two types of PUFAs: omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids. Vegetable oils are rich in omega-6 fatty acids. This is a highly inflammatory fatty acid which competes with the phenomenal benefits of omega-3’s (which are found in fish, eggs, and grass-fed beef). Americans today are consuming abundant amounts of harmful omega-6 fats and not enough omega-3 fats. This has set us up for a health disaster. Paradoxically, over-consumption of “heart healthy” omega-6 fats increases our risk of several diseases including heart disease (the very thing we were trying to avoid by using this label).

Secondly, “heart healthy” vegetable oils use harsh chemicals, like hexane, and need to be deodorized to make them palatable. They also become rancid quickly and the crop is often sprayed with pesticides prior to harvest. These attributes may not affect your heart directly, but they certainly disrupt the way your body functions on several levels.

The other concern with the heart-healthy label (aside from vegetable oils) is that they are often low in fat. And we have already learned that low-fat foods are usually code for “high sugar.”

Low-Calorie:

This label is all the rage with diet bars and single-serving cookie snacks. Ever notice that the low-calorie label is mainly seen on snack foods, which are inherently unhealthy? This is a ploy to get you to buy them by justifying that you’re not doing much damage since it’s “low-calorie.” The truth is, calories should not be a deciding factor behind any food purchases. The exception might be for athletes in training who must maintain a certain level of fitness and performance. But keep in mind that sports nutrition is a different segment of nutrition entirely, where calories and carbs are the ultimate measure of a food’s value. However, once you enter the world of whole-food nutrition, the importance of calories and carbs takes a back-seat (with the exception of the keto diet and some detox or fasting regimens). Calories, after all, do not measure the quality of food. If a person equates low-calorie to good health, they’ll soon find that a serving of low-calorie cookies is “healthier” than an avocado! Rather than looking at calories, look at the value that the food will give you. Does it contain a variety of nutrients? Is it low in sugar and sodium? Are the ingredients unprocessed or minimally processed? Answers to these questions are a better gauge of food quality than the number of calories it contains.

Low-Carb:

This label can get you in trouble. As much as low-carb diets can be helpful for many people, this label doesn’t indicate the quality of the carbs. Check the ingredients to see whether it contains refined or processed grains.

Multigrain:

The multigrain label can be very misleading for health-conscious consumers. It simply means there is more than one type of grain in the food, but it doesn’t specify the quality of the grains. Oftentimes, multigrain labels contain refined grains.

Natural:

It is not uncommon to see this label on a variety of food products. For products that contain plant foods, this label simply means that at one point the manufacturer began with a whole plant food such as wheat or an apple. However, the rest of the manufacturing process is as far from “natural” as you can get. When it comes to meat products, the term “natural” means the meat was minimally processed and contains no artificial ingredients or added color. It does not mean the animal was raised in a pasture. In fact, statistically, it was likely raised in a crowded feedlot and received routine antibiotics.

Organic:

The organic label is designated by the USDA and requires farmers to meet a high standard of quality. Certified organic foods contain little to no pesticides or antibiotics and do not use genetically modified organisms (GMO’s). Thus, this label usually indicates a healthy food item containing whole-food ingredients. But be wary of believing that every organic food is healthy. Indeed, you will find the organic label on cookies, cheese crackers, and hydrogenated oils. Unhealthy foods should be avoided regardless of whether they are organic.

Gluten-Free:

Similar to the organic label, those foods labeled as gluten-free aren’t necessarily healthy. These days you can find processed gluten-free cookies or toaster waffles, which are just as bad for you as the conventional version.

No Added Sugar:

Be careful with this one. This label means no sugar was added on top of the natural sugar already present in the food. Natural sugars can still spike blood glucose (depending on the type of food) such that fruit servings should be limited to two per day. Another caution with this label is that the food likely contains artificial sweeteners that don’t technically qualify as “sugar.”

Made With Whole Grains:

Unlike other labels, this label at least indicates quality. The trap here is that the food may contain very little whole grains. Check the ingredients list to see if any whole grains are listed as the first three ingredients. If not, then the amount of whole grains (regardless of the label) is negligible.

Fortified or Enriched:

Although these terms seem similar, they have different meanings. Fortified foods are those that have had nutrients added to them that otherwise are not naturally present. Examples include milk fortified with vitamin D, fruit juices fortified with calcium, or rice fortified with iron, zinc and several vitamins.

Enriched foods are those that have lost nutrients during processing and thus have them added back into the food. Examples are in breads and pastas where B vitamins are initially lost and then added back in.

The problem with both enriched and fortified foods is that the nutrients added to them are synthetic versions (folic acid is the synthetic version of folate for example). Synthetic nutrients are not usually absorbed and utilized properly as compared to their natural form. Furthermore, most fortified foods and all enriched foods are heavily processed anyways. There are better ways to get the nutrients you need: through eating whole, unprocessed foods.

Fruit-Flavored:

This label is different from natural flavors in that it’s created using chemicals to mimic the taste of fruit. You’ll see this label a lot in fruit yogurts or soft drinks. Synthetic flavoring is also used to create imitation extracts for baking. Imitation vanilla flavoring comes from distilling wood-tar or tree resin, while imitation almond flavoring comes from benzaldehyde, a chemical used in dyes and perfumes.

Nutrition Facts By the Numbers

Now that you know what to look for on the front of food packaging, you can quickly determine if the food should be put back on the shelf. If it passes the first inspection though, now we can read the nutrition facts label and the ingredients list.

Know Your Serving Size!

The first thing listed on the nutrition label will be the serving size. This is probably the most important piece of information as it tells you what to expect in the nutrients that follow it. Servings sizes don’t have to be killjoys though. They actually help keep you out of trouble (if you follow them).

For example, if you read that a bottle of flavored Yerba Matte has 20 grams of sugar you might be concerned (at least I hope you would be). However, if you read the serving size and it says ½ bottle, then you know that if you drink half the bottle you’d be cutting that sugar content in half. Never assume that the entire container is a single serving (this is especially true with beverage bottles).

Likewise, if you see a low amount of sodium on a box of crackers and think to yourself that it is worthy of eating, great. But if you then eat half the box in one sitting, you’ve just given yourself a surge of sodium over and above what’s healthy (not great).

The key in both instances is to follow the serving size! If you eat (or drink) indiscriminately and to your heart’s content, you will have consumed way more sugar, sodium, carbs, fat, etc than you bargained for.

Nutrient Label Highlights:

Moving down the label, there are a few items we should always look for, as well as an idea of how much is too much per serving. The actual amounts (in grams) is more helpful for us than the percent daily value (listed as %DV). This is because nutrition labels are based on a 2,000 calorie diet. However, many people of healthy weight consume less calories than this, making the percent daily value inaccurate for their needs. Let’s take a look:

-Sugar: less than 10 grams

It should be noted that the negative effect of sugar in your body is lessened when you pair it with fiber. This not only makes the case for eating whole fruit rather than pure fruit juice, but it also means that packaged foods with high fiber will help moderate the effect of the sugar that’s in it. This doesn’t give license to reach for sugary, high-fiber foods! But it does help give peace of mind when a healthy, fiber-rich food happens to contain 10 grams of sugar.

-Fat: this is divided into saturated fat and trans fat. Usually, these numbers will be low for most packaged foods so there isn’t a reason to worry.

Trans fats were banned by the FDA in 2018 although there are exceptions to the ban. Naturally occurring trans fat is found in meat and dairy in very small amounts. Other foods use partially hydrogenated oil (trans fat) such as margarine, fried food, and baked goods. Be aware that the FDA allows labels to say “0g of trans fats” if a food contains less than 0.5 grams. You can locate these foods by looking for “partially hydrogenated oil” in the ingredients list. Unfortunately, quantities of healthy fats are not listed on nutrition labels. It would be quite helpful to know whether a food contains unsaturated fats, so hopefully this will be added in the future.

-Fiber: at least 3-4 grams, but the more the better!

-Sodium: less than 200 mg

Micronutrients:

The next section of the nutrition facts label (right above the ingredients list) will list the micronutrients and their associated percentage of daily value per serving. Nutrition facts labels are now required to list vitamin D and potassium in this section, whereas vitamins A and C are no longer required to be listed. Calcium and iron are also commonly listed although not required. After that, food packages will have varying lists of vitamins and minerals depending on what’s in them.

As a general rule, however, it is good to choose food that has at least 15% of its daily value per serving. Do be aware that synthetic versions of vitamins and minerals should not be the main source of your nutrient intake. Your body will absorb and use much more of these nutrients when they’re packaged in fresh fruits, vegetables, and whole grains rather than in boxes.

Ingredients to Watch For:

Moving down the nutrition label we come to the ingredients list. There are a few things to point out here that will help guide your food purchases.

The ingredients list is ordered based on the quantity of that ingredient, from highest to lowest. As a rule of thumb, the first three ingredients listed make up the majority of the food, with the fourth ingredient onwards comprising only a small percentage of each serving. Because of this, make sure those first three ingredients are whole foods rather than any refined grains, sugar, or hydrogenated oils.

Another rule of thumb is to aim for foods that have less than 10 ingredients listed. Any more than that usually means the product is highly processed.

A common recommendation when reading ingredients lists is that if you cannot pronounce an ingredient or if it sounds like something you might have encountered in your high school chemistry class, then it’s best not to buy it. Ingredients must be identifiable. Oftentimes, you’ll see things like “cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12).” This means they’re listing vitamin B12 but also giving you the specific form it comes in. Ingredients listed like this may make things tough to pronounce but the vitamin it refers to is not a harmful ingredient. By the way, cyanocobalamin is the synthetic version of vitamin B12 and is the version used in processed foods (whether fortified or enriched). While not harmful on its own, it is not usually well-absorbed.

Lastly, it is good to be aware of the various ways of saying “sugar” in ingredients lists. All of these forms of sweeteners are counted in the “added sugars” label.

Common Names for Sugar:

Anything with the name “sugar” in it (like beet sugar, date sugar, or confectioners sugar). Also, evaporated cane juice is a fancy way of hiding sugar in the ingredients.

Common Names for Syrup:

Anything with “syrup” in the name (like carob syrup, high-fructose corn syrup, maple syrup, or rice bran syrup). Also, honey and agave nectar classify as syrup.

Common Names for Other Added Sugars:

molasses, cane juice crystals, crystalline fructose, malt powder, fructose, maltose, barley malt, dextran, fruit juice concentrate, ethyl maltol, galactose, glucose, corn sweetener, disaccharides, and maltodextrin.

Grocery shopping is the first step in deciding how well your body is going to function for the next week. Wise purchasing habits at the corner market today gives you abundant health benefits at the kitchen table over several days. The tricky part about wise purchasing habits is that many of us believe we are doing it correctly. Too often, it’s the clever food advertisers who are the wise ones. Knowing the facts behind misleading health claims on flashy packaging helps you decide whether a food is worthy of your shopping cart or worthy of the store shelf. Further, knowing the importance of serving sizes, and what to look for on nutrition labels and ingredients lists will allow you to choose the healthiest options in the store. Of course, the best way to avoid being misled by sneaky advertising is to focus on foods that haven’t been altered by scientists. After all, fruits and vegetables don’t have ingredients lists!

by Kirsten Chesney | Apr 16, 2020 | Nutrition

Most of us are likely limiting our trips to the grocery store these days, in order to abide by the Shelter in Place recommendations. However, limited trips inevitably make it difficult if you’ve forgotten to purchase a food item from your list. It also means potentially running out of a staple before the week is up. Here are some ways to boost the nutrient content and availability in the foods we have, without having to return to the store or buy special ingredients.

1) Add a greens powder to smoothies. There are many greens powders out there. These tubs look similar to protein powder but they contain antioxidant-rich phytonutrients found in various vegetables and some fruit. Common ingredients are wheatgrass, barley grass, chlorella, broccoli, spinach, kale, Acai berry, dandelion, flax seeds, beets, maca, and various herbs. Choose an organic variety and use one scoop in your smoothies to instantly increase your intake of greens!

2) Opt to steam or saute rather than boil or fry. Steaming and sauteing are cooking methods that generally retain the highest level of nutrients for your vegetables. Boiling often allows nutrients to leach into the water, which is then discarded before eating. Steaming prevents vegetables from contacting water, thus they retain their nutrients. The benefits of sauteing are in the olive oil. Olive oil increases the absorption of phytonutrients, like beta carotene and polyphenols, found in vegetables. It is also a healthy fat and contains antioxidants in its own right. Be aware to use low to medium-low heat when sauteing with olive oil.

3) Roast your tomatoes. Cut and unpeeled. Lycopene, the phytonutrient in tomatoes, is made more available for our bodies when tomatoes are cut and roasted. It’s important to not peel a tomato, nor discard its seeds, as this is where most of their antioxidants come from.

4) Soak your grains. Soaking whole grains, preferably overnight, increases the availability of micronutrients including, iron, zinc, calcium, and vitamins C, A, and the B’s. Additionally, soaking grains will help with fiber digestion. Rinse and discard the soaking water when you’re ready to cook.

5) Freeze your own vegetables. If you want to stock up on produce but the frozen aisle is already wiped clean, opt to freeze your own. Stock up on fresh produce and freeze any quantity you won’t be eating right away. Be sure to blanch and shock vegetables first: boil them briefly, drain, and then submerse in ice water. Dry them completely then store in an air-tight container or large freezer bag. Be sure to date them. Frozen vegetables are good for about a year. Good vegetables to freeze include: broccoli, Brussel sprouts, onions, corn, spinach, kale, corn, squash, and tomatoes.